Over a decade ago, the front page of ‘the economist’ once had a nuclear mushroom cloud with the caption ‘Cyberwar: the threat from the internet’. A dramatic way to encapsulate the vision of how we perceived the impact of such a threat. Since then the term ‘cyberwar’ is bandied around a lot without any real connotation as to what we are talking about. Sometimes we are simply referring to large scale cybercrime but it’s clear from the outset that there’s a lack of criteria for defining it. Traditional warfare has clear parameters: casualties, territorial gains and military engagements, often assigned to a clear winner and loser. Not so with Cyberwarfare. In general terms we can define it as an activity that begins in cyberspace but that has real ramifications in the physical space, impacting societies in the way that physical war does.

On February 24, 2022, Russia began its war of aggression and launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine in what they termed a ‘special military operation’. It is the only time where Russian propaganda matched Western Intelligence, with both parties thinking Kyiv (the capital) would be captured in 3 days and the West would effectively be funding an insurgency while Russia took control of the entire country. Clearly the Ukrainians had a different opinion, because the large Russian formations, strung out over hundreds of miles, ill-supplied with poor logistics were stopped, defeated and beaten back. Now, one year and a half into the conflict the Russian army is on the defensive, losing ground by the day after taking enormous casualties in men and material.

Russia and Ukraine are both considered well equipped in cyber capability and there is a history of Russian cyberwarfare activity against Ukraine (more on that later). Alongside the kinetic conflict, a cyber conflict evolved and we have the first time in history where two belligerents are engaged in a full-scale kinetic conflict in real space and a similar engagement in cyberspace. Would cyberwarfare finally become as important as kinetic warfare? Would it impact the conflict?

Almost from the outset, Ukraine had excellent support from its allies in the cyber-sphere. Western vendors, such as CloudFlare, AWS , Cisco and Microsoft stepped in to provide network connectivity and resilience, protective tools such as WAFs, IPS/IDS, firewalls and DDOS protection. They also provided cloud resiliency and helped Ukraine migrate it’s on-premise data centers into the cloud as they were at risk of physical destruction from the invasion. Western governments also supplied cyber-aid in the form of threat indicators, monitoring and support, leveraging their CERT teams where possible. On the offensive side, Ukraine created the largest volunteer hacker organization ever seen. The ‘IT army of Ukraine’ as it was known became a prolific force in cyberspace, at its peak numbering upwards of 200,000 people, although this number has decreased drastically as the war has rumbled on and now numbers an average of 20-30 thousand individuals (still a formidable force). This was effectively classed as an auxiliary arm to Ukrainian cyber command, acting as an offensive force against Russian infrastructure.

On the Russian side, fewer assets were in play. The GRU and FSB (analogues to the CIA and FBI) were always active in cyberspace, but quite limited in their resourcing since they were never equipped for large scale conflict. There is no analogue to the IT army of Ukraine on the Russian side since the support on the international stage and even domestically for the Russian position was quite low. A few organized criminal groups such as Conti did explicitly align for a time with the Kremlin, but in the case of Conti this actually caused their implosion, as many Ukrainians formed part of their organization and didn’t agree with the invasion at all.

Onto the activity of these different cyber belligerents and we have an almost one-sided story. Aside from the Viasat hack in the early days of the war, while there have been many attempts, the Russian side has scored few successes (one could argue this is an almost exact parallel to the kinetic invasion) with only 19 successful hacks being recorded on the Ukrainian side, and this exclusively against civilian technical infrastructure.

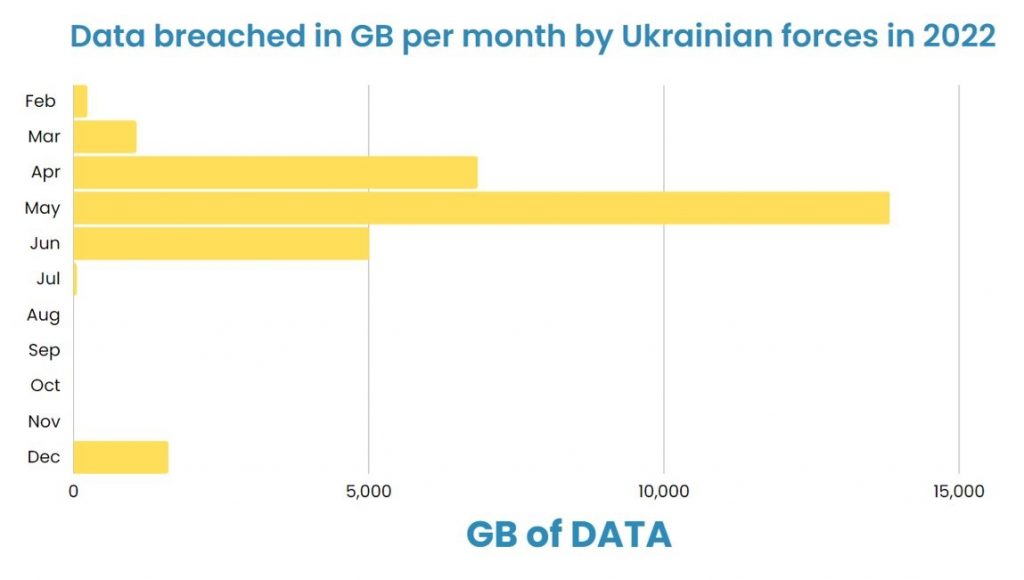

The Ukrainian side is a completely different picture. In 2022, in terms of data alone, the Ukrainian side caused close to 30 terabytes in breaches from the Russian federation.

To put that into perspective, if you took the top 10 breaches of 2022 (Uber, Twitter, Revolut bank, etc.) which equate to hundreds of millions of personal details breached, these only equate to about 15% of what was breached from the Russian federation in 2022.

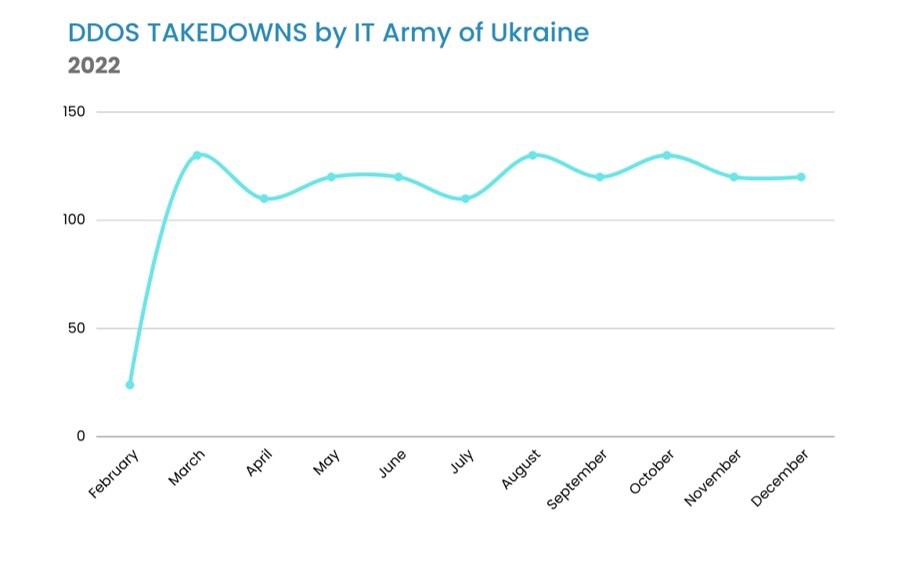

Breaches side, there have also been DDOS attacks that have been successfully launched against Russia by the IT army of Ukraine on an almost daily basis. On average, three DDOS attacks are launched per day at Russian targets, and this has been happening consistently since the invasion in February 2022.

If we look at the targets that have been leaked, we also notice they are quite significant: Roskomonadzor, Central Bank of Russia, Yandex, Gazprom, Transneft, Russian Radia, United Russia party… the target list reads out like a who’s who of the most critical Russian government departments and industrial companies that power the Russian economy. No site is spared. The IT army of Ukraine had also published their methodology on target selection and it boils down to targeting business related sites during weekdays (banking, customs, etc.) and leisure related sites on the weekends (airlines, hotels, cinemas, etc.) so that the impact on society is at its maximum.

The impact has been felt by Russia, so much so that the head of its security council, Dmitri Medvedev stated that they needed better defenses against Cyber-attacks – a rare admission of failure by what is usually a wall of propaganda.

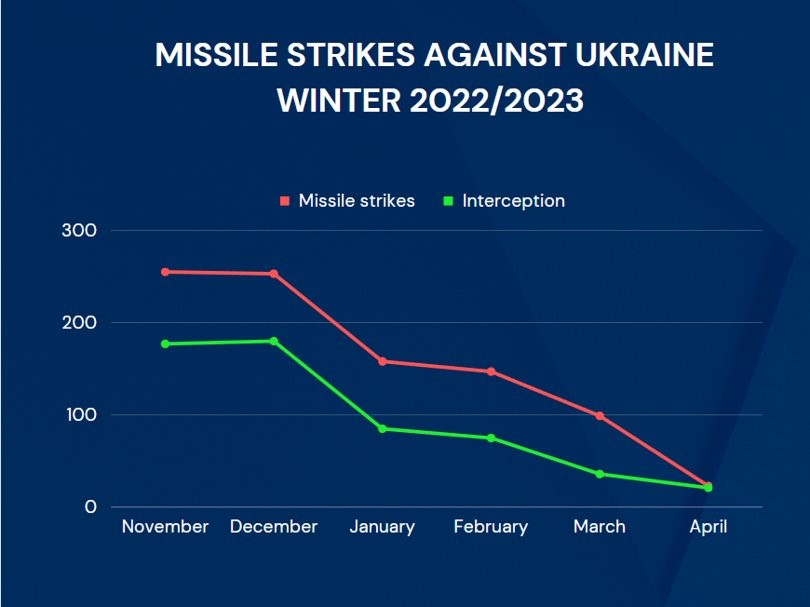

But lets take a step back and look at the conflict through the lens of cyberwarfare again. A common trope that we often hear is that cyberwarfare could be used to shut down a national power grid, rendering a society helpless as they have no electricity to function. This was indeed attempted and Russia has scored successful limited power outages against Ukrainian power infrastructure in the past using cyber-attacks, both in 2015 (a 6 hour power outage affecting 250,000 people) and in 2016 (70 minute outage affecting 100,000 people). In a country of 44 million people these equate to nothing from a statistical level and an MIT paper suggested the 2015 attack took 19 months to even prepare and launch. Evidence from this conflict suggests the Russians again attempted attacks against Ukrainian energy infrastructure but none were successful. Not only were the Russians unsuccessful in shutting down the Ukrainian power grid using cyber attacks, they also failed to do it using kinetic warfare. From November 2022 until April 2023, throughout the Ukrainian winter, the Russians openly stated they would ‘freeze Ukraine’ by destroying or disabling energy infrastructure, especially in the capital city.

Over five months the Russians launched hundreds of drones and over a thousand cruise and ballistic missiles at Ukrainian energy infrastructure. Just to illustrate how extreme that level of ordnance is, the only other notable missiles power that we have metrics for (The USA) has only launched 2000 cruise missiles since 1991 in all conflicts combined. In five months the Russians launched half this amount, and while the missiles themselves are often inaccurate and were also often shot down, the operation to eliminate Ukrainian energy infrastructure ultimately proved a failure. By February 2023, Ukrenergo declared they had no energy deficit, and by April they had so much electricity they were re-exporting it to the EU. A salient reminder that not only is it exceedingly difficult and ineffectual to try and disable energy infrastructure using cyber-attacks, it is as difficult, if not more so to do it using kinetic means, even if the belligerent has substantial firepower available.

So lets take a look at the impact of the cyberwar in Ukraine on the conflict itself. Even after conducting blistering attacks against Russian infrastructure and tearing down dozens of sites a month, will it influence or impact the conflict at all? The answer is no. The outcome of the conflict in Ukraine will not be decided in cyberspace, nor will the cyberwar have any impact on the kinetic conflict at all. The outcome of the conflict in Ukraine will be impacted by how many 155mm artillery shells Ukraine receives, or how soon they get F-16’s, not by how many DDOS takedowns or breaches are leveled against the Russian federation. Cyberwarfare, while at a conceptual level may seem threatening, in the perfect example of a side by side kinetic and cyber conflict, the ultimate impact is nothing. Cyberwarfare remains a myth and will continue to do so until societies and their militaries are connected centrally, online and more autonomously – and that is a long, long way away. ![]()

Alex Haynes

Leave a Comment