Ask any cyber intelligence analyst about today’s major threats, and they will likely launch into a discussion about hacking groups in China, Iran, North Korea, or Russia. Indeed, state-sponsored threat actors in these countries are highly sophisticated and have wreaked havoc on global network infrastructure. However, the cybersecurity industry continues to overlook other areas of the world. This information gap constitutes a problem in an increasingly interconnected society. The sovereignty of national borders becomes obsolete when cybercriminals can target victims located anywhere with just a click of a button. Therefore, the threat intelligence industry needs to better track events occurring in areas outside of the aforementioned countries.

Latin America is a region that deserves closer scrutiny from the industry. Central and South America are home to a complex cyber threat landscape and base of hackers. The threats in this region is largely fueled by political and economic instability. For instance, Latin America has one of the world’s highest rates of cryptocurrency adoption due to historically unpredictable national currencies and general public distrust in the banking sector (Contxto). This is important because the large-scale cryptocurrency usage and online banking activity increases attack vectors and potential rewards for cybercriminals.

The cyber threat landscape in Latin America is a double-edged sword, for the region can be characterized as both a perpetrator and victim of cyber-attacks. On the one hand, there has been a notable uptick in advanced cyber operations orchestrated by malicious actors. On the other hand, private sector entities, government agencies, and journalists in Latin America are increasingly victimized. Indeed, the region is home to a complex web of cyber activity that affects business operations. Thus, cyber threats in Latin America are worthy of analysis and discussion.

The Perpetrators: Cybercriminal Groups in Latin America

One of the primary factors distinguishing Latin American cybercriminals from their counterparts in Russia or China is that their operations are highly localized. In general, threat actors in Latin America operate on a smaller scale, focusing their operations on private sector entities, government agencies, intelligence services, and journalists based in the same area. They prefer “tried and true” methods of network exploitation, such as spearphishing, use of open-source, multi-stage payloads, and other living off the land techniques. These groups tend to be financially motivated and opportunistic in nature. While some Latin American APTs have orchestrated attacks based on political messaging, there is not much evidence to indicate that they are state-sponsored or even state-aligned.

Meet Machete (a.k.a. Ragua or Arkantos Live Control), one of the most well-known and advanced APTs associated with the region. This threat actor is likely located in Latin America, based on the Spanish language artifacts found in their source code. Believed to have been operating since at least 2010, Machete typically targets military agencies and political institutions in Venezuela, Ecuador, and Colombia (Kaspersky SecureList). However, the group has also exploited victims in the U.S., Europe, and Asia. Machete is known for espionage, network surveillance, and targeted social engineering.

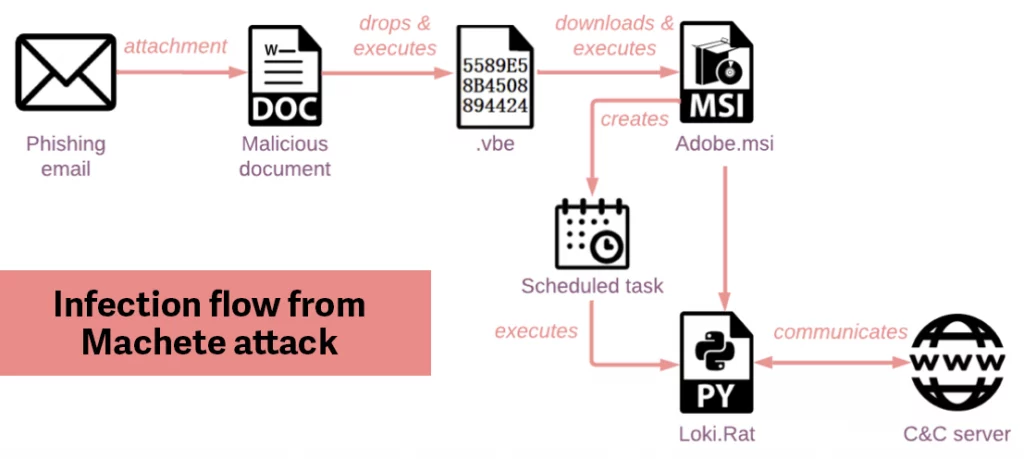

In March 2022, shortly following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, researchers discovered a massive phishing campaign launched by Machete against financial institutions in Nicaragua. To gain initial access into the victims’ systems, Machete sent a spearphishing email containing a clever lure document which contained malicious macros (Check Point Research). The document contained a legitimate article published by the Russian Ambassador to Nicaragua regarding Russia-Ukraine relations (El 19 Digital). Once victims downloaded the document and activated the macros, the attackers installed a custom backdoor version of Loki.Rat, an open-source malware previously used by Machete (Accenture). This malware can stealthily perform a number of actions within a victim environment, including keylogging, credential harvesting, and taking screenshots of a user’s device.

The Victims: Latin American Entities Targeted by Global APTs

Next, let’s look at how Central and South America have been victimized by large-scale cyber-attacks. Over the past few years, threat actors based in other areas of the world have focused their operations in Latin America, causing major disruption to business operations. Government agencies, military services, and financial institutions are most frequently targeted. Additionally, given the region’s large-scale dependence on online banking, international APT groups are beginning to target the banking sector.

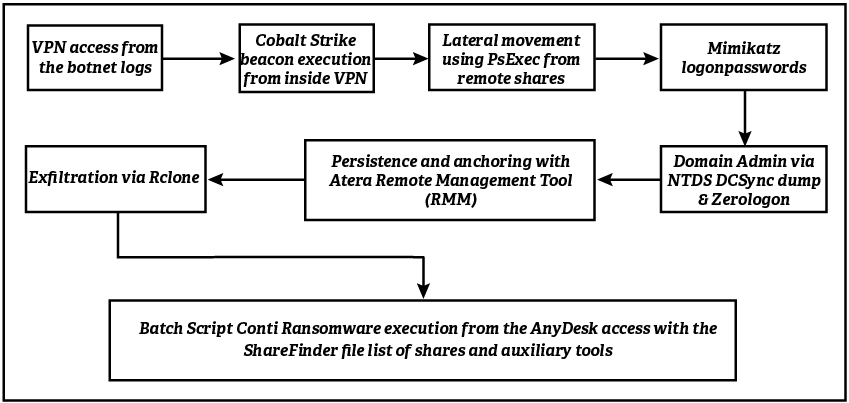

In January of 2023, the Costa Rican Ministry of Public Works and Transportation (MOPT) confirmed it had been hit by a ransomware attack (Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación, Tecnología y Telecomunicaciones – MICITT). The hackers encrypted 12 of MOPT’s servers, which caused all of the ministry’s computers to lose connectivity. The threat actors utilized Conti ransomware to orchestrate the campaign against MOPT; however, researchers have not yet attributed the attack to a particular group.

The latest incident in Costa Rica comes just months following another larger-scale ransomware attack which paralyzed the government’s digital infrastructure. The breach prompted President Rodrigo Chaves to declare a state of national cybersecurity emergency (Sistema Costarricense de Información Jurídica). Conti, a notorious Russian ransomware gang that orchestrated the attack, ordered the Costa Rican government to pay a ransom of USD 20 million. When Costa Rica refused to comply, the hackers posted 670 GB (approximately 97% of the stolen data) to a leak site (The Record).

Conclusion

If cybercrime is so prevalent in Latin America, why is it so infrequently reported by the broader industry? There are some important factors to consider. First of all, threat actors in the region tend to have less resources and operate on a smaller scale compared to well-funded adversaries. Therefore, their operations do not have the same level of disruption as do larger groups based elsewhere in the world. This is especially notable in their targeting – Latin American hackers tend to exploit victims located within the region. While some groups, including Machete, have operated on a global scale, they are not bombarding U.S. infrastructure to the extent other APTs are. Thus, the industry has adopted an “out of sight, out of mind” mentality.

The cyber threat environment in Latin America is rapidly evolving, catalyzed by economic issues, political volatility, and rising organized crime. The region is home to both the hackers and the hacked. Cybercriminals are capitalizing on Latin America’s rapid digitalization by executing coordinated campaigns against consumers, businesses, and governments. These threat actors are beginning to expand their operations outside of the region, as seen in the appearance of Brazilian banking trojans in Europe (Kaspersky SecureList).

On the other hand, countries in Latin America are continuously victimized. In 2022, Brazil was ranked the fourth most breached country in the world, exceeding even the U.S. in terms of affected users (ZDNet). Additionally, foreign investment in the region is growing. Nations with historically robust cyber capabilities, such as Russia, China, and Iran, are investing in Latin American digital infrastructure. The Venezuelan government, for example, adopted Chinese tracking technologies (Reuters) and organized meetings with federal Russian cybersecurity officials (Reuters). This type of influence can directly impact the region’s cyber capabilities.

The cyber community should expect to see growing sophistication in Latin American cybercrime. From Mexico to Argentina, APT groups continue to hack network systems and challenge industry assumptions of their capabilities. These hackers are contributing to the global cyber problem, and in order to address it, the tech community must give Latin America a seat at the table. ![]()

Approved for Public Release; Distribution Unlimited. Public Release Case Number 22-02304-8. © 2023. The MITRE Corporation. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Kate Esprit

Leave a Comment